You are viewing this post: Who Is May-Wan Kao Details To Know On Charles K. Kao Wife? The 47 Top Answers

Are you looking for an answer to the topic “Who Is May-Wan Kao Details To Know On Charles K. Kao Wife“? We answer all your questions at the website Bangkokbikethailandchallenge.com in category: Bangkokbikethailandchallenge.com/digital-marketing. You will find the answer right below.

Keep Reading

May-Wan Kao is the wife of American-British-Chinese electrical engineer Charles K. Kao. Let’s learn more about May-Wan Kao in this article.

May-Wan Kao is Chairman of the Charles K. Kao Foundation.

The Charles K. Kao Foundation for Alzheimer’s Disease is chaired by Kao.

Charles K. Kao has received various awards and honors, including the Nobel Prize in Physics.

Who Is Charles K. Kao’s Wife, May-Wan Kao?

Charles K. Kao’s wife, May-Wan Kao, is Chair of the Charles K. Kao Foundation.

She is British-born Chinese. They married in London in 1959.

Kao met his future wife Gwen May-Wan Kao after graduating from London when they were both working as engineers.

According to his memoirs, Kao was a Catholic who attended the Catholic Church while his wife attended Anglican Communion.

#MerryChristmas pic.twitter.com/7oTKIx1n3z

— Charles K Kao Fdn (@CKK_Fdn) December 22, 2015

May-Wan Kao’s Children. Where Is She Now?

May-Wan Kao has two children, both of whom live and work in California’s Silicon Valley.

She claims that being active and helping run a charity named after her husband helped her cope with her loss.

During the weekdays, she gets up at 7 a.m. and goes jogging with her assistant on the Chinese University campus, where she continues to live in the staff quarters.

She plays tennis twice a week and admits to being a fan of Korean soap dramas.

Find Out May-Wan Kao’s Age

The age of May-Wan Kao is still unknown to us. Comparing her age to her husband’s, she appears to be in her 80s.

advertisement

Her husband died at the age of 84.

More information on her actual age and date of birth will be released shortly.

The confirmation of the pledges was publicly performed on the #CUHKLibrary pic.twitter.com/uztgo1cwSK on the morning of December 12

— Charles K Kao Fdn (@CKK_Fdn) December 15, 2015

Explore May-Wan Kao’s Net Worth

May-Wan Kao’s net worth is still being verified.

Consering her occupation and her position as Chair of the Charles K. Kao Foundation, we can estimate her net worth in the millions of dollars.

If we add her husband’s net worth to hers, we estimate it will be more than a million dollars.

More information on her net worth will be released soon.

May-Wan Kao’s Husband Charles

May-Wan Kao’s husband, Charles Kuen Kao, was an electrical engineer and physicist who pioneered the use of fiber optics in telecommunications.

Before moving to London to study electrical engineering, he grew up in Taiwan and Hong Kong.

The father of fiber optics: Charles Kao, 2009 Physics Prize Laureate.

Kao presented fibers made of very pure glass that can transmit information over long distances. His invention made fiber optic telecommunications possible. #WorldDevelopmentInformationDay pic.twitter.com/2G7bmMtvDU

— The Nobel Prize (@NobelPrize) October 24, 2020

He also attended Shanghai World School at the Shanghai French Concession, where he studied English and French.

She married Prof. Charles Kao, the “Father of Fiber Optics” after graduating from London in 1955.

Prof. Kao made international headlines in 2009 when he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics and revealed that he suffers from Alzheimer’s.

Did Charles K Kao have any kids?

She was an engineer in the coil section. We were married in 1959 and our children were born, a son in 1961, and a daughter in 1963.

How old is May Wan Kao?

…

Charles K. Kao.

| The Honorable Sir Charles K. Kao GBM KBE FRS FREng | |

|---|---|

| Born | Charles Kuen KaoNovember 4, 1933 Shanghai, China |

| Died | September 23, 2018 (aged 84) Sha Tin, Hong Kong |

Is Charles K Kao alive?

When was May Wan Kao born?

Ms May Wan Wong, more publically known as Gwen Kao, was born in the UK in 1934 to immigrant parents from Guangdong Province, in the south of China.

How old is Charles K Kao?

Where was Charles Kao born?

Kao, considered the father of fiber optics whose innovations revolutionized global communication and laid the groundwork for today’s high-speed internet. Charles Kuen Kao was born on this day in 1933 in Shanghai, China.

When was Charles Kao born?

Charles Kao, in full Charles Kuen Kao, Pinyin Gao Kun, (born November 4, 1933, Shanghai, China—died September 23, 2018, Hong Kong), physicist who was awarded the Nobel Prize for Physics in 2009 for his discovery of how light can be transmitted through fibre-optic cables.

Who invented fiber Internet?

Charles Kuen Kao is known as the “father of fiber optic communications” for his discovery in the 1960s of certain physical properties of glass, which laid the groundwork for high-speed data communication in the Information Age.

Which contemporary scientist is credited with laying the conceptual foundations of optical fibre technology?

Charles Kuen Kao, a Shanghai-born scientist, was awarded one-half of the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physics for his trailblazing work in the field of fibre-optics communication. “In 1966, Charles K. Kao made a discovery that led to a breakthrough in fibre optics.

When did Charles Kao invent fiber optics?

In the 1960s Charles Kao presented a solution: fibers of very pure glass transported sufficient light. Together with laser technology, his solution has made telecommunication using optical fibers possible.

Why optical Fibres are used in communication?

Fiber optics (optical fibers) are long, thin strands of very pure glass about the size of a human hair. They are arranged in bundles called optical cables and used to transmit signals over long distances. Fiber optic data transmission systems send information over fiber by turning electronic signals into light.

How does fiber optics work?

Fiber-optic cables transmit data via fast-traveling pulses of light. Another layer of glass, called “cladding,” is wrapped around the central fiber and causes light to repeatedly bounce off the walls of the cable rather than leak out at the edges, enabling the single to go farther without attenuation.

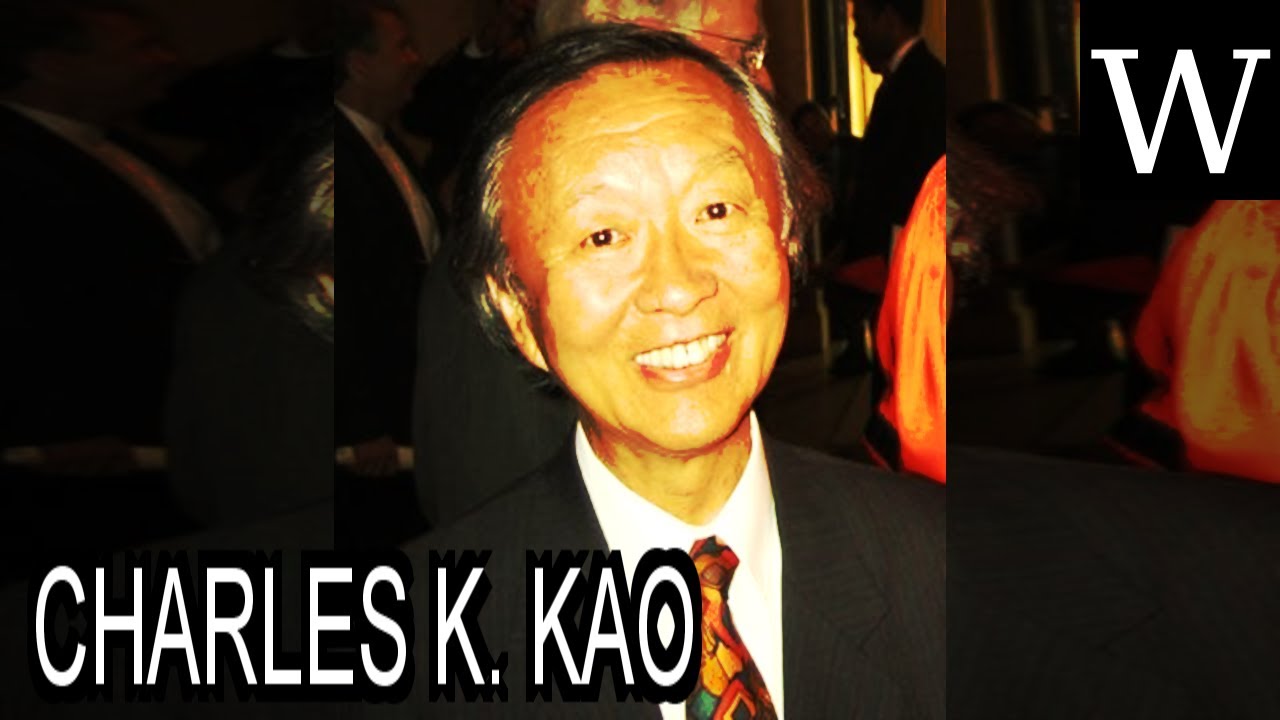

CHARLES K. KAO – WikiVidi Documentary

Images related to the topicCHARLES K. KAO – WikiVidi Documentary

See some more details on the topic Who Is May-Wan Kao Details To Know On Charles K. Kao Wife here:

Who Is May-Wan Kao? Details To Know On Charles K. Kao Wife

Kao’s wife, May-Wan Kao, is the chairman of the Charles K. Kao Foundation. She is a British-born Chinese woman. They married in London in 1959.

Source: 44bars.com

Date Published: 1/23/2021

View: 1916

Obituary – Who Was Charles K. Kao? – Wife May-Wan Kao …

Details About Charles K Kao Wife May-Wan Kao. Charles K Kao’s wife May-Wan Kao is also an engineer who worked at Standard Telephones and …

Source: 247newsaroundtheworld.com

Date Published: 1/29/2022

View: 1301

Who was Charles K. Kao Wife? May-Wan Kao; His Bio, Cause …

May-Wan Kao is best known for being the wife of the late, Charles K. Kao, an electrical engineer, and physicist who pioneered the …

Source: glob-intel.com

Date Published: 7/7/2021

View: 2743

Charles K. Kao – Wikipedia

Sir Charles Kao Kuen GBM KBE FRS FREng (November 4, 1933 – September 23, … Charles K. Kao cropped 2.jpg. Charles K. Kao … Spouse(s). Gwen May-Wan Kao.

Source: en.wikipedia.org

Date Published: 1/5/2021

View: 2751

Charles K. Kao – Biographical

Charles K. Kao Biographical

family background

The Kao family hails from a township called Zhangyan in Jinshan District near Shanghai, China1. As landowners, the family would have been considered prosperous. The sons of each generation would be well educated in the style of the time. My knowledge of the family genealogy only goes back to my grandfather.

Grandfather Kao Hsieh2 also bore the courtesy name Kao Ch’ui Wan3. He was a man of letters, famous for his beautiful poems, rendered in Chinese calligraphy; the combination of poetry and calligraphy is an art form of the east. A Confucian scholar, he was a book collector and also a prominent member of the Nan She (Southern Society). Other family members were also active in the society; Their aim during the 1911 Chinese Revolution was to help overthrow the ruling Qing dynasty. A museum now established in the city exhibits his work and also tells the story of the political activities in which the man took part. He was liberal.

Grandfather had four sons and two daughters. My father, Kao Chun Hsin, was not the eldest of the sons. The eldest would have remained in town to look after the family’s possessions and affairs; there these duties always fell. He was the third son. These sons grew up when modern times came to China. After a good education in Shanghai, my father went to Michigan Law School for a year. Before leaving for the United States, a marriage was arranged with a petite lady from one of the families of the social circle. She was left to await the return of the adventurous man. Coming from a family that was as modern as it was intellectually savvy, the new wife was educated and a poet herself.

Those were the years when offspring of the few wealthier middle-class families in China ventured to Paris, to London, to New York to deepen their experiences and studies. When they returned to China, they were greeted with great enthusiasm.

After returning from the United States, Kao Chun Hsin, then only in his mid-twenties, was appointed a Chinese judge at the International Court of Justice. He shared the bench with established judges from Western countries. With this prestigious appointment, he and his young wife moved to Shanghai, where they participated in the city’s social life.

The first child born to the couple was a daughter, who was followed by a son two years later. misfortune struck. In a measles epidemic, both children fell ill and both died of complications, the older child at the age of ten, the younger at the age of eight. The mother was small-boned and of delicate, fragile appearance. The birth would not have been easy. In the years following the tragedy, she had miscarriage after miscarriage. I was finally born in 1933, fortunately a healthy child for my parents. My younger brother Timothy joined the family four years later.

Due to the earlier loss of the two older siblings, my brother and I lived a very spoiled and sheltered life. Nannies kept constant watch. Since my parents were busy with dinner parties and social events, we only saw them as if for a daily royal audience. Later, home teachers came to give us lessons. The basic lesson plans were readings from the well-known classics, the Four Books,4 which we learned to recite by heart. A second tutor taught English.

When I was ten years old, I was finally sent to school. The driver dropped me off in the school yard and told me to wait and someone would tell me where to go. I had never seen so many children running around so wildly in a crowd and standing there wide-eyed.

A bell rang and soon the playground was empty save for a lonely child. A friendly looking lady appeared and took me to my class. Maybe it was home tutoring, or starting regular school late, or an overly cautious and protective upbringing, but I certainly never became a talkative person. As an adult, I’m not always comfortable with small talk in social gatherings. I must have inherited my father’s gentle ways.

The elementary school I attended in Shanghai was a very liberal one, founded by scholars returning from an education in France. The children of leading families were enrolled there, including the son of a well-known man who is considered the top gangster of the underworld!

By now the family had a home that was within the French Concession. The International Settlements were located in an area within the city where various western powers had authority. These areas were generally kept away from the bustle of the metropolis and provided a haven from the human poverty of China. Locals called this area Shili Yangchang (a ten-mile strip of foreign glasses). When the Japanese invaded China in the 1930s, these areas were off-limits to the invaders.

The family was shielded from the horrors that unfolded. With the chaos of war, the courts were suspended and social gatherings dried up. My parents stayed at home more during this time and we developed a closer relationship with them. We played bridge and card games together to while the hours away.

Ending the war with Japan did not bring peace. Soon the Red Army, which had fought against the nationalist government, was at the gates of the city. My father made the decision to leave. In the family games of bridge, the topic was often discussed and the various options pondered. Moving to Chungking5 or going to relatives in Taiwan, or maybe there were relatives living in Hong Kong as well?

In 1948, after gathering up some belongings, the family boarded a ship sailing from Shanghai on a gray, gloomy, rainy day. The Bund’s famous waterfront slowly faded from view and that was the last we saw of our hometown for many years.

A brief stay in Taipei, the capital of Taiwan, convinced my father that Hong Kong would be a better place to escape. With the help of relatives on my mother’s side in Hong Kong, the family found a small apartment and my brother and I were enrolled at St Joseph’s College, where our cousins also studied. As English was the preferred language of instruction, the local dialect of Cantonese was not a requirement and I never felt the need to learn the language.

At 48, my father felt too old to study for the law exams that would qualify him to practice in Hong Kong. Instead, he took a job as a company legal advisor and also taught some Chinese law courses at local colleges. He became known in Hong Kong as an expert interpreter of ancient Chinese laws. There were still some cases of family inheritance and such matters that would require such expert advice.

I did well academically, but didn’t do much track or physical education during my five years at St. Joseph’s College. My former classmates in later life reported that they remembered me as a quiet person who didn’t get involved in the rough and tumble boy games. I almost got straight A’s in the matriculation exams, which enabled me to apply for admission to the University of Hong Kong. However, the university was still in some disarray after the war and not all faculties were functioning. I wanted to study electrical engineering. Great Britain beckoned and the British Council in Hong Kong was helpful. In 1953 I went to England on board a P&O liner.

I enrolled at Woolwich Polytechnic in London to take the Baccalaureate exams, which I passed with ease. I felt so comfortable at Woolwich Polytechnic that I did not apply to the other more prestigious colleges at London University and continued to study there for my Bachelors degree. In 1957 I graduated with a B.Sc. in electrical engineering. At that time, the degrees were awarded as first, second, pass or fail. Because I spent more time on the tennis court than with my books, my degree was a second.

It was necessary to find a job immediately. Financing my studies was a heavy burden for my father. I joined Standard Telephones & Cables (STC), a UK subsidiary of International Telephone & Telegraph Co (ITT) in North Woolwich, a factory across the River Thames. As a trainee, I was rotated through different departments for a year before realizing that I liked working in the microwave department. After two more years, I decided it was time to move on and applied for a teaching position at Loughborough Polytechnic.

During my three years at STC, I met and married Gwen, a fellow engineer who worked in the lab upstairs from my workbench. So we went to Loughborough for an interview, I got the job and we immediately started looking for a home. When we found newly built homes we put down a deposit and drove back to give our notices to STC.

However, it shouldn’t be

Someone in senior management had noticed how I had been working on the microwave projects and felt that the promise I was showing should not be lost on the company. The offer came immediately to allow me to transfer to the STL research lab in Harlow. As an added incentive for me to stay, a position would also be found for Gwen at the new location. Loughborough needed reassurance and solicitors went to work trying to get the bail on the house back. The offer was too good to pass up, and my future was destined to follow this new course. I stayed with ITT Corp and worked at various locations in the UK, US and Europe for the next thirty years.

In those years my parents emigrated to us in Great Britain in 1967. They were both in their late 60s and older at the time, but were still able to live independently. They were happy to have a grandson born in 1961 and a granddaughter born in 1963.

In 1970, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, CUHK, called. Would I come to college to set up an electronics department? STL agreed to grant a two-year leave of absence, which then became four years. I was able to see the first group of students graduating and also set up a graduate program. During this period, 1970-1974, annual summer vacations were taken to return to STL to keep abreast of developments in optical fiber research. It was also an opportunity to see my parents who stayed in Harlow.

By 1974, the project I had launched with the now famous 1966 article published in the IEE Proceedings had progressed into the pre-production development phase. Around them had grown an industry that went full force to revolutionize telecommunications systems around the world. ITT wanted me to be part of the team again for this endeavor.

So the young family was uprooted again, this time moving to the ITT facility in Roanoke, Virginia, USA. I was promoted to chief scientist, then to vice president and director of engineering, responsible for ITT’s electro-optical products division. During my years in the US, I continued to travel to other research labs around the world to discuss advances, promote the work, and keep up to date with the latest developments. It was a busy time. I used to drop by to visit my parents in the UK.

In 1976 my mother died at the age of 76. My widowed father, who visited Roanoke once or twice, preferred to live in Britain and this situation continued until he finally moved in with us in his eighth decade when we were back in Hong Kong.

By the 1980s, fiber optics was being deployed in large numbers around the world and the industry had grown into a giant. The communication capacity had grown exponentially. In 1982, I was appointed senior scientist at ITT, responsible for all research and development activities, and I moved to the Advanced Technology Center in Connecticut, USA. This position was specially created and gave me the freedom to do whatever I thought was important for ITT. To demonstrate the ultimate frontiers of optical communication technology, I advanced the Terabit Optoelectronics Technology Project to explore the technologies that could achieve terabit per second transmission capacity. The project, which involved a consortium of ten universities and institutions, aimed for a goal three orders of magnitude higher than the state of the art at the time. In 1985, I was appointed Director of Corporate Research at ITT. During this time, many innovations were developed by creative minds to take advantage of the increased capacity to send information through the system. The internet was born.

In 1986, CUHK called again. This time the request was to accept the post of rector of the university, the contract is scheduled to begin in 1987. In British terminology this post is called Vice-Chancellor of the University.

The second move to Hong Kong came as ITT Corp began selling all of its US engineering operations to Alcatel, a French company. After thirty years, it was a sad moment to say goodbye to long-time colleagues.

I was the third vice chancellor of the CUHK for nine years. It has been an interesting and challenging time, both for Hong Kong preparing to regain sovereignty from China, and for the higher education sector, which has seen massive expansion and quality improvement. During these years I strove to establish research more prominently as part of the normal work of the faculty, to establish contacts with many leading institutions in the US and UK, and to set the university on a path to becoming a better known institution. in competition with the best institutions. I was particularly pleased about the founding of the Faculty of Engineering, in which information technology played a major role. A faculty for educational sciences was also founded in these years. A number of research institutes were also established. The size of the university has almost doubled in just a few years, and a fourth undergraduate college has been established.

My job at university was to create space for people to grow. Essentially what I had done was create situations in which people would like to take responsibility. As a result, the university has grown as a whole: everyone contributes what they are supposed to do because they feel responsible for it and the environment allows them to do so. I created the space at the right time for talents to perform within the university and take them to a new level of development.

The rapid expansion of the tertiary education sector and the accompanying increase in government funding have enabled us to do many things to become a top university. The most gratifying change has been a scholarly atmosphere on campus—people are pursuing important things because they believe such things are important.

It was perhaps natural for my advice to be sought and for me to get involved in technology issues in the community, particularly information technology. I was able to play a role in setting up an internet exchange in Hong Kong (a bit of a novelty then and still a useful service today) and promoting the establishment of the Hong Kong Science Park.

My father died in 1996 just before I retired from university – a year before colonial Hong Kong was returned to China. My father’s ashes were brought back to England to be buried with my mother – in a cemetery in Harlow. After a year of speaking tours in Southeast Asia, I stayed in Hong Kong and started my own consulting company. I have been called to a number of companies as a non-executive director.7 In 2009 I moved to California to be closer to my two children.

Vignettes from childhood and working life memories

I had an argument with Lo in my classroom. We attacked each other with our calligraphy brushes, smearing black ink on our faces and hands. The teacher was shocked. Lo, my mother warned me, was the son of a wicked man. I should be careful not to argue with the boy again. Otherwise the school was fine. We sang French songs. The calligraphy teacher was very encouraging. This stroke is beautiful and is marked with a red dot. But this one is crooked and unbalanced, it gets two red points!

I made a good friend in elementary school who liked to play with me at home. We made our driver buy all sorts of chemicals. We read scientific journals, experimented together, and made phosphorus mud balls to throw at stray cats and dogs. The mud balls would explode with a bang, scaring the animals to death! From glass bottles and the like I would make the funnels and beakers needed. I had bottles of cyanide and concentrated acids. One day when I was boiling nitric acid, the bottle exploded and the concentrated acid spattered onto my little brother’s pants. It burned the cloth off completely but luckily didn’t end up on his skin! My parents were furious and confiscated all my chemicals including the cyanide. I wonder where they dumped that stuff.

One day my father brought home a large round yellow disk of food that he told us was called “cheese” that foreigners ate. Food was scarce so we ate it but it tasted very weird. When we walked outside, we sometimes passed a large, tall building with Japanese soldiers standing outside the door. My parents told us to hurry by as people were being killed there and bow to the soldiers.

It was sad to leave Shanghai, but I was fourteen years old and ready for new adventures. The war with Japan was also exciting. As we crouched under the desks, we could hear the aerial combat in the sky above us. Peering from below I even got a glimpse of the American planes chasing the Japanese planes and diving in after them!

So the Shanghai waterfront faded away and we went to Hong Kong. The schooling there was easy and the book work was not difficult at all. The class went on a field trip and some of my classmates got lost in the hills until it was pitch black and they could see “tigers”! I wasn’t in that group, but now when we have a class reunion, the boys will relate their adventures with enthusiasm and lots of laughter. So my years in Hong Kong flew by and I was set to embark on my next adventure all by myself.

On the ship to England to study electrical engineering, I shared a cabin with three others. Two worked for the Hong Kong government and went to England to take some courses relevant to their job, meteorology and water treatment respectively. The third was a professor of mathematics. During the six-week voyage, the professor taught me quantum mechanics. He also took some other young students and me under his wing. When we stopped in Singapore he accompanied us to his friend’s house and taught us all to eat hot curry and wash down the fiery food with beer.

I was nineteen years old and had never left my family to be alone before. Everything was a new experience. To put my foot on the ground in Port Said so I could tell myself I’d been to Africa to cross the Strait of Gibraltar and say I’d seen Europe and the Sahara to find England a cold and gray land ! I didn’t think eleven long years would pass before I would see my parents again.

The British Council staff met me and arranged accommodation for me with a landlady in a house on Plumstead Commons, near Woolwich Poly. Her house was old and big, with rooms for several lodgers. We all ate breakfast and dinner together under the stern eyes of the landlady. After World War II, food was still scarce and the slices of meat served at dinner were so thin that they were transparent when held up to the light! After such a meager meal we all moved out into the ‘fresh air’ but the real reason was to buy some fish and chips which we hungrily taunted on the way back up the hill. The habit remains; I still love fish and chips.

After graduating from Polytechnic in 1957 I joined STC and had to walk to work every day through the tunnel under the Thames. My first project was to build an amplifier and I got my books out to study the theories. My boss came over and told me to put the books away, just do it. The schoolwork is to train the brain to think intelligently. There was no need to revise the theories any more!

I met my future wife at work. She was an engineer in the coil department. We married in 1959 and our children were born, a son in 1961 and a daughter in 1963. At that time we were living in Harlow and working at STL.

The research was fascinating work and in 1966 I published the now famous seminal paper Dielectric-fibre Surface Waveguides for Optical Frequencies. This research would spawn a whole new industry over the next twenty years.

People asked me if the idea came suddenly, eureka! I had worked on microwave transmissions since graduating. The theories and limitations were ingrained in my brain. I knew we needed a lot more bandwidth and I kept thinking about how this could be accomplished.

Transmitting light through glass is an old, old idea. It has been used in years past to shine light through a glass rod for entertainment, for decoration, for short distances in operations, but it has not been possible to use it over the long distances required for telephony. Light passing through a glass rod fades to nothing after a very short distance of a few meters. Efforts by many research labs to find a way to transmit light long distances have been desperate as the public, spurred by media reports of hopeful technological advances, expected increasingly exotic services.

I played around with what resulted in the light not penetrating glass. With the invention of the laser in the 1950s and subsequent developments, there was an ideal light source that could emit pulses of light in a digital stream of zeros and ones, represented by off and on states of the pulse.

Ideas don’t always come about in the blink of an eye, but through diligent trial and error experiments that take time and thought.

Charles Kuen Kao Awards and Honors 1. American Ceramic Society Morey Award, 1976. Citation: for outstanding contribution to glass science and technology. 2. Stuart Ballantine Medal of the Franklin Institute, U.S.A., 1977. Citation: for conceptual work on optical fiber communication systems. 3. Rank Prize of the Rank Trust Fund, UK, 1978. Citation: for pioneering fiber optic communications. 4. IEEE Morris H. Liebmann Memorial Award, U.S.A., 1978. Citation: for bringing communications to practice at optical frequencies through the discovery, invention, and development of the material, techniques, and configurations for fiber optic waveguides, and particularly for recognizing and through careful measurements in bulk glass proved that silica glass could provide the requisite low optical loss needed for a practical communications system. 5. Ericsson Foundation L.M. Ericsson International Prize, Sweden, 1979. Citation: for seminal contributions to the long-distance transmission of information by optical fibers. 6. Gold Medal from the Armed Forces Communications and Electronics Association, U.S.A., in 1980. Citation: for contribution to the application of fiber optic technology in military communications. 7. IEEE Alexander Graham Bell Medal, USA, 1985. Citation: for pioneering contributions to fiber optic communications. 8. Marconi International Fellowship of the Marconi Foundation, U.S.A., 1985. Citation: for contributions to a revolution in communication techniques in the form of fiber optic technology. 9. Columbus Medal from the City of Genoa, Italy, 1985. Citation: for significant scientific discovery. 10. Foundation for Communication and Computer Promotion C&C Award, Japan, 1987. Mention: for pioneering work in fiber optic communications. 11. Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa, from the Chinese University of Hong Kong, 1985. Citation: for outstanding contributions to fiber optic communications. 12. IEE Faraday Medal, UK, 1989. Citation: for recognition of continued outstanding work in optical communications, including early work on determining the feasibility of fiber optic communications systems and defining the parameters involved. 13th American Physical Society International Prize for New Materials, U.S.A., 1989. Citation: for the contribution to materials research and development that led to practical low-loss optical fibers, one of the cornerstones of optical communications technology. 14. Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa, University of Sussex, UK, 1990. Citation: for important contributions to the understanding and application of optoelectronic communication techniques. 15. Honorary doctorate from Soka University, Japan, 1991. Note: for the promotion of science and culture. 16. Doctor of Engineering, Honoris Causa, University of Glasgow, UK, 1992. Citation: for recognition of his achievements in the field of engineering. 17. Gold Medal of The International Society for Optical Engineering (SPIE), U.S.A., 1992. Citation: for recognition of his pioneering work and his many contributions to the field of fiber optic communications. 18. Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire (CBE), in 1993. Citation: for his distinguished academic record and seminal work on optical fibers 19. Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa, University of Durham, UK, im Year 1994 Citation: for recognition of his pioneering work in the field of telecommunications. 20. Gold Medal of Engineering Excellence from the World Federation of Engineering Organizations (WFEO) in 1995. Award: for recognition of his pioneering work and development in fiber optics of great importance to all mankind. 21. Doctorate from the University of Griffith University, Australia, in 1995. Mention: for recognition of his outstanding contributions to the world of international learning and university education. 22nd Japan Prize in Information, Computing and Communications Systems from the Science and Technology Foundation of Japan, 1996. Citation: for recognition of his pioneering research in the field of high-bandwidth, low-loss fiber optic communications. 23. Prince Philip Medal of the Royal Academy of Engineering, UK, 1996. Citation: in recognition of his seminal contributions to the invention of optical fiber for telecommunications and for his leadership in its technical and commercial realization; and for his outstanding contribution to higher education in Hong Kong. 24. Doctor of Telecommunications Engineering, Honoris Causa, The University of Padova, Italy, in 1996. Citation: for recognizing his pioneering work in the field of telecommunications engineering. 25. Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa, University of Hull, U.K., 1998. 26. Doctor of Science, Honoris Causa, Yale University, U.S.A., 1999. Citation: for recognition of his achievements as an inventor and educator. 27. Charles Stark Draper Prize, National Academy of Engineering, U.S.A., 1999. Citation: for recognizing the design and invention of optical fibers for communications and for developing manufacturing processes that made the telecommunications revolution possible. 28. Doktor der Naturwissenschaften, Honoris Causa, The University of Greenwich, U.K., im Jahr 2002. 29. Doktor der Naturwissenschaften, Honoris Causa, Princeton University, U.S.A., im Jahr 2004. 30. Nobelpreis für Physik, Königlich Schwedische Akademie der Wissenschaften , Schweden, 2009. Zitierung: für bahnbrechende Leistungen bei der Übertragung von Licht in Fasern für die optische Kommunikation.

1. Ein Großteil der Familieninformationen wird von Gwen Kao rekonstruiert, basierend auf ihrem eigenen Wissen und ihren Erinnerungen an Charles‘ familiären Hintergrund.

2. Im modernen Pinyin Gao Xie.

3. Im modernen Pinyin Gao Chuiwan.

4. The Great Learning, die Doctrine of the Mean, die Analekten des Konfuzius und der Mencius waren die Kerntexte des konfuzianischen Lernens.

5. Jetzt bekannt als Chongqing.

6. Der Kanzler ist der Gouverneur (nach der Wiedererlangung der Souveränität durch China, der Chief Executive), der in einer weitgehend zeremoniellen Rolle dient.

7. Anmerkung von Gwen Kao: Im Jahr 2005 wurde die Alzheimer-Krankheit bestätigt, und im Moment gibt es keine Heilung dafür.

Von Les Prix Nobel. Die Nobelpreise 2009, Herausgeber Karl Grandin, [Nobelstiftung], Stockholm, 2010

Diese Autobiografie/Biografie wurde zum Zeitpunkt der Preisverleihung verfasst und später in der Buchreihe Les Prix Nobel/Nobel Lectures/The Nobel Prizes veröffentlicht. Die Informationen werden manchmal mit einem vom Preisträger vorgelegten Nachtrag aktualisiert.

Copyright © Nobel-Stiftung 2009

Um diesen Abschnitt zu zitieren

MLA-Stil: Charles K. Kao – Biographisch. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach AB 2022. 12. Juli 2022.

Charles K. Kao

Chinese scientist and Nobel laureate (1933–2018)

kao In accordance with Hong Kong custom, the Western-style name is Charles Kao and the Chinese-style name is Kao Kuen. In this Hong Kong name is the surname. In accordance with Hong Kong custom, the Western-style name is Charles Kao and the Chinese-style name is Kao Kuen.

This article uses Western naming order when mentioning individuals.

Sir Charles Kao Kuen [5][6][7][8][9] (November 4, 1933 – September 23, 2018) was an electrical engineer and physicist who pioneered the development and use of optical fibers in telecommunications. In the 1960s, Kao created various methods to combine optical fibers with lasers to transmit digital data, laying the foundation for the development of the Internet.

Kao was born in Shanghai; his family moved to Hong Kong when he was about 15 years old. He grew up in Taiwan and Hong Kong before moving to London to study electrical engineering. In the 1960s Kao worked at Standard Telecommunication Laboratories, the research center of Standard Telephones and Cables (STC) in Harlow, and it was here that he laid the foundation for optical fiber in communications in 1966.[10] Known as the “Godfather of Broadband,”[11] the “Father of Fiber Optic,”[12][13][14][15][16] and the “Father of Fiber Optic Communication,”[17] he continued his work in Hong Kong at the Chinese University of Hong Kong and in the United States at ITT (the parent company of STC) and Yale University. Kao received the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physics for “pioneering in the transmission of light in fibers for optical communications.”[18] In 2010 he was knighted by Queen Elizabeth II for “services to fiber optic communications”.[7]

A permanent resident of Hong Kong[19], Kao was a citizen of both the United Kingdom and the United States[1].

Early life and education[edit]

Charles Kao was born in Shanghai in 1933[20]: 1 then a separate administrative area.[21][22] He studied Chinese Classics at his brother’s home under a tutor.[23][20]:41 He also studied English and French at the Shanghai World School (上海世界學校) in the Shanghai French Concession[24] founded by a number of progressive Chinese educators, including Cai Yuanpei.[25]

Kao’s family moved to Taiwan in 1948 and then to British Hong Kong[20]:1[26] where he completed his secondary education (Hong Kong School Certificate Examination, a predecessor of HKCEE[27])[28] at St. Joseph’s College in 1952. He received his undergraduate degree in Electrical Engineering from Woolwich Polytechnic (now the University of Greenwich)[29] and received his Bachelor of Engineering[20]:1[30][Non-primary source needed]

He then continued his research and obtained his PhD in Electrical Engineering from the University of London in 1965 with Professor Harold Barlow of University College London as an external student while working at Standard Telecommunication Laboratories (STL) in Harlow, England, the research center for standard telephones and cables.[ 2] It was there that Kao did his first breakthrough work as an engineer and researcher, working alongside George Hockham under the direction of Alec Reeves.

Ancestry and family[edit]

Kao’s father Kao Chun-Hsiang [zh] (高君湘)[20]: 13 was a lawyer who received his Juris Doctor from the University of Michigan Law School in 1925.[31] He was a professor at Soochow University (then in Shanghai) Comparative Law School of China.[32][33]

His grandfather, Kao Hsieh, was a scholar, poet, artist[23] and a leading figure in South Society during the late Qing Dynasty.[34] Several writers, including Kao Hsü, Yao Kuang [zh] (姚光), and Kao Tseng [zh] (高增), were also close relatives of Kao.

His father’s cousin was the astronomer Kao Ping-tse[23][35] (the Kao Crater is named after him[36]). Kao’s younger brother, Timothy Wu Kao (高鋙), is a civil engineer and professor emeritus at Catholic University of America. His research focuses on hydrodynamics.[37]

Kao met his future wife Gwen May-Wan Kao (née Wong; 黃美芸) after graduation in London when they worked together as engineers at Standard Telephones and Cables.[20]:23 [38][unreliable source?] They is British Chinese .[20]: 17 They married in London in 1959,[20]: 15–17 [39] and had a son and a daughter,[39] both of whom live and work in Silicon Valley, California.[11 ] [38][40][unreliable source?] According to Kao’s autobiography, Kao was a Catholic who attended the Catholic Church while his wife was taking Anglican Communion.[20]: 14–15

Academic career[edit]

Fiber optics and communications[edit] [41] A bundle of fused silica fibers for optical communications, which is the de facto world standard. Kao also first publicly suggested that high-purity fused silica was an ideal material for long-distance optical communication.

In the 1960s, Kao and his collaborators at Standard Telecommunication Laboratories (STL), based in Harlow, Essex, England, pioneered the development of optical fiber as a telecommunications medium by showing that the high losses of existing optical fiber were due to contamination that glass, and not from an underlying problem with the technology itself.[42]

When Kao first joined the optical communications research team in 1963, he took notes summarizing the background situation[43] and the technology available at the time, and identifying the key people[43] involved. At first, Kao worked in the team of Antoni E. Karbowiak (Toni Karbowiak), who worked under Alec Reeves on the study of optical waveguides for communications. Kao’s task was to study fiber attenuation, for which he collected samples from various fiber manufacturers and also closely examined the properties of bulk glasses. Above all, Kao’s study convinced him that the impurities in the material caused the high light losses of these fibers.[44] Later that year, Kao was appointed head of the electro-optics research group at STL.[45] He took over the optical communications program from STL in December 1964 because his supervisor Karbowiak left the institute to take up the chair in communications at the School of Electrical Engineering at the University of New South Wales (UNSW) in Sydney, Australia.[46]

Although Kao succeeded Karbowiak as manager of optical communications research, he immediately decided to abandon Karbowiak’s plan (thin film waveguides) and change research direction altogether with his colleague George Hockham. They not only took optical physics into account, but also the material properties. The results were first presented by Kao to the IEE in London in January 1966 and published further in July by George Hockham (1964–1965 worked with Kao). [47][a] This study first theorized and proposed to use fiber optics to implement optical communications, the ideas described (particularly structural features and materials) are largely the basis of today’s fiber optic communications.

“What Kao did in Harlow changed the world and created a backbone for the internet. He was the father of fiber optics.” —David Devine of Harlow Museum on Kao’s pioneering work in fiber optics at STC’s Standard Telecommunication Laboratories in Harlow[48]

In 1965[45][49][b] Kao concluded with Hockham that the basic limit for glass light attenuation is below 20 dB/km (decibels per kilometer, is a measure of the attenuation of a signal over a distance), which is an important threshold for optical communication.[50] However, at the time of this determination, optical fibers typically exhibited a light loss of up to 1,000 dB/km and even more. This conclusion opened the intense race for low-loss materials and suitable fibers to meet these criteria.

Kao, along with his new team (including T.W. Davies, M.W. Jones and C.R. Wright) pursued this goal by testing different materials. They precisely measured the attenuation of light with different wavelengths in glasses and other materials. During this time, Kao pointed out that the high purity of fused silica (SiO 2 ) made it an ideal candidate for optical communications. Kao also explained that contamination of the glass material is the main cause of the dramatic drop in light transmission inside the fiber, not fundamental physical effects like scattering as many physicists thought at the time, and that such contamination could be removed. This led to a worldwide investigation and production of high-purity glass fibers.[51] When Kao first suggested that such optical fibers could be used to transmit information over long distances and could replace copper wires used for telecommunications at the time, his ideas were widely disbelieved. later people realized that Kao’s ideas revolutionized the entire communications technology and industry.[52]

He also played a leading role in the early development and commercialization of optical communications.[53] In the spring of 1966, Kao traveled to the United States but failed to interest Bell Labs, which at the time was a competitor to STL in communications technology. He then traveled to Japan and gained support.[54] Kao visited many glass and polymer factories and discussed the techniques and improvements in glass fiber production with various people, including engineers, scientists, and businessmen. In 1969, Kao with M.W. Jones measured the intrinsic loss of bulk fused silica at 4 dB/km, which is the first evidence for ultratransparent glass. Bell Labs began seriously considering fiber optics.[54] As of 2017, optical fiber losses (both bulk and home sources) are only 0.1419 dB/km at a wavelength of 1.56 µm.[55]

Kao developed important techniques and configurations for fiber optic waveguides and contributed to the development of various fiber types and system devices that met both civilian and military[c] application needs and peripheral supporting systems for fiber optic communications.[53] In the mid-1970s he did pioneering work on the fatigue strength of glass fibers.[53] When he was appointed ITT’s first principal scientist, Kao launched the “Terabit Technology” program to address the high frequency frontiers of signal processing, hence Kao is also known as the “father of the terabit technology concept”.[53][56] Kao has published more than 100 articles and received over 30 patents,[53] including the waterproof high-strength fibers (with M. S. Maklad).[57]

From an early stage in the development of fiber optics, Kao clearly favored singlemode rather than multimode systems for long-distance optical communications. His vision was later followed and is now applied almost exclusively.[51][58] Kao was also a visionary of modern underwater communication cables and was instrumental in promoting this idea. He predicted in 1983 that the world’s oceans would be littered with fiber optics, five years before such a transoceanic fiber optic cable first became operational.[59]

Ali Javan’s introduction of a stationary helium-neon laser and Kao’s discovery of the light-loss properties of fibers are now recognized as the two major milestones in the development of fiber-optic communications.[46]

Later work[edit]

Kao joined the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) in 1970 to establish the Department of Electronics, which later became the Department of Electronic Engineering. During this time, Kao was the lecturer and then the chair professor of electronics at CUHK; he built both undergraduate and graduate degrees in electronics and supervised the graduation of his first students. The School of Education and other new research institutes were established under his direction. In 1974, he returned to ITT Corporation (STC’s parent company at the time) in the United States, working in Roanoke, Virginia, first as Chief Scientist and later as Director of Engineering. In 1982 he became the first ITT Executive Scientist and was primarily based at the Advanced Technology Center in Connecticut.[15] There he was an associate professor and fellow at Trumbull College, Yale University. In 1985, Kao spent a year in West Germany at the SEL Research Center. In 1986, Kao was corporate director of research at ITT.

He was one of the first to study the environmental impact of land reclamation in Hong Kong, presenting one of his first studies at the Association of Commonwealth Universities (ACU) conference in Edinburgh in 1972.[60]

Kao was Vice Chancellor of the Chinese University of Hong Kong from 1987 to 1996.[61] As of 1991, Kao was an independent non-executive director and member of the Audit Committee of Varitronix International Limited in Hong Kong.[62][63] From 1993 to 1994 he was President of the Association of Southeast Asian Institutions of Higher Learning (ASAIHL).[64] In 1996, Kao made a donation to Yale University and the Charles Kao Fund Research Grants were established to support Yale’s study, research, and creative projects in Asia.[65] The fund is currently managed by the Yale University Councils on East Asian and Southeast Asian Studies.[66] After retiring from CUHK in 1996, Kao spent his six-month research leave at Imperial College London’s Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering; from 1997 to 2002 he also worked as a visiting professor in the same department.[67]

Kao served as Chairman and member of Hong Kong’s Energy Advisory Committee (EAC) for two years and retired from that position on July 15, 2000. Kao was a member of the Council of Advisors on Innovation and Technology of Hong Kong, appointed April 20, 2000.[70] In 2000, Kao co-founded the Independent Schools Foundation Academy, located in Cyberport, Hong Kong.[71] He was its founding chairman in 2000 and resigned from the ISF board in December 2008.[71] Kao was a keynote speaker at IEEE GLOBECOM 2002 in Taipei, Taiwan.[72] In 2003, a special appointment made Kao a full professor in the Electronics Institute of the College of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science at National Taiwan University.[72] Kao then served as Chairman and CEO of Transtech Services Ltd., a Hong Kong-based telecommunications consultancy. He was Founder, Chairman and CEO of ITX Services Limited. From 2003 to January 30, 2009, Kao was an independent non-executive director and member of the Audit Committee of Next Media.[73][74]

Awards[edit]

Kao has received numerous awards such as Nobel Prize in Physics[75], Grand Bauhinia Medal, Marconi Prize, Prince Philip Medal, Charles Stark Draper Award, Bell Award, SPIE Gold Medal, Japan International Award, Faraday Medal, James C. McGroddy Prize for new materials……

honors [edit]

Social and academic recognition[ edit ]

Honorary title[ edit ]

Awards[edit]

Kao donated most of his award medals to the Chinese University of Hong Kong.[76]

namesake[edit]

Other [edit]

Later life and death[ edit ]

Kao’s international travels led him to believe that he belonged to the world and not to any country.[140][141] An open letter published by Kao and his wife in 2010 later clarified that “Charles studied in Hong Kong for his high school, he taught here, he was the vice chancellor of CUHK and has also retired here. So he belongs to Hong Kong.”[142]

Pottery was a hobby of Kao. Kao also enjoyed reading wuxia (Chinese battle fantasy) novels.[143]

Kao had suffered from Alzheimer’s disease since early 2004 and had speech difficulties, but had no trouble recognizing people or addresses.[144] His father suffered from the same disease. As of 2008, he resided in Mountain View, California, USA, where he moved from Hong Kong to live near his children and grandson.[11]

When Kao received the Nobel Prize in Physics on October 6, 2009 for his contributions to the study of light transmission in optical fibers and fiber communication,[145] he said: “I am absolutely speechless and never expected such an honor.”[146] Kaos Ms. Gwen told the press that the award will primarily be used for Charles’ medical expenses.[147] In 2010, Charles and Gwen Kao established the Charles K. Kao Foundation for Alzheimer’s Disease to raise awareness of the disease among the public and patients to support.

In 2016, Kao lost the ability to keep his balance. In the final stages of his dementia, he was being cared for by his wife and had no intention of using life support or performing CPR.[148] Kao died on September 23, 2018 at Bradbury Hospice in Hong Kong at the age of 84.[149][150][151][152]

work [edit]

Notes [edit]

^a: Kao’s main job was to study light loss properties in optical fiber materials and determine whether or not they can be removed. Hockham’s studied light loss due to discontinuities and fiber curvature.

^ b: Some sources show around 1964,[153][154] for example: “By 1964, Dr. Charles K. Kao identified a critical and theoretical specification for long-distance communication devices that standard 10 or 20 dB of light loss per kilometer.” by Cisco Press.[153]

^c: In 1980 Kao was awarded the Gold Medal of the American Armed Forces Communications and Electronics Association “for his contribution to the application of fiber optic technology in military communications”.[53]

^ d: The United States National Academy of Engineering membership website refers to Kao’s country as the “People’s Republic of China”.[87]

^e: OFC/NFOEC – Fiber Optic Communications Conference and Exhibition/National Fiber Optic Engineers Conference [133]

References[edit]

Obituary – Who Was Charles K. Kao – Wife May-Wan Kao Family and Death Cause

“The word ‘visionary’ is overused, but I think in the case of Charles Kao it’s entirely appropriate because he really did see a world connected by light to the medium of fiber optics,” said John Dudley, a researcher in fiber optics based in France and former President of the European Physical Society. “And I think today’s society owes him a lot for this work.”

dr Kao and a colleague, working in Britain in the late 1960s, played a crucial role in discovering that the fiber optic cables then in use were limited by impurities in their glass. They also outlined the potential capacity of the cables to transmit information – one far superior to that of copper wires or radio waves.

His death was confirmed by the Hong Kong-based Charles K. Kao Foundation for Alzheimer’s Disease, which he and his wife Gwen Kao founded in 2010. The foundation declined to provide a cause but said Dr. Kao found out he had the disease in 2002.

Obituary – Who Was Charles K. Kao? – Wife May-Wan Kao Family and cause of death – A Nobel laureate in physics whose research revolutionized the field of fiber optics in the 1960s and helped lay the technical foundations for the information age died in Hong Kong on Sunday. He was 84.

According to his Wikipedia, her two children live in Silicon Valley, California. Furthermore, he mentioned in his autobiography that he was a Catholic who attended the Catholic Church while his wife attended Anglic Communion.

She is British Chinese. The couple married in 1959 and had two children. They are parents of a daughter and a son.

May-Wan Kao, wife of Charles K. Kao, is also an engineer and worked at Standard Telephones and Communications. The couple first met there after Charles graduated from the University of London.

There he first worked as an engineer and continued to develop his career, which eventually earned him the prestigious Nobel Prize in Physics.

He did not stop there and continued his studies. He earned his Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering from the University of London in 1965 while working at Standard Telecommunications Laboratories.

In 1952 he completed his secondary education at St. Joseph’s College. He earned a bachelor’s degree in engineering from Woolwich Polytechnic, now the University of Greenwich.

He was born on November 4, 1933 in Shanghai. He studied Chinese, English and French before his family moved to Taiwan in 1948 and eventually to British Hong Kong.

Charles K. Kao’s cause of death was not mentioned in his obituary. However, he was said to have been diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 2002. He died in Hong Kong on September 23, 2018 at the age of 84.

They used a green fiber laser to transfer data from one end of the Doodle to the other, representing its contribution to the field of science.

Charles K. Kao was a noted electrical engineer and physicist who pioneered the use of fiber optics in telecommunications. Raised in Hong Kong, then under British rule, he moved to England after matriculation. There he studied electrical engineering and eventually moved to Standard Telephones & Cables. He was later transferred to STC’s research lab, where his job was to study fiber attenuation. Very quickly he realized that the loss of light in fibers was caused by impurities contained in them. Over time, he developed various techniques to fuse optical fibers with lasers so that digital data could be transmitted without much loss, laying the foundation for the development of the Internet. For this discovery he was not only called the “Godfather of Broadband”, but also received numerous awards and honors, including the 2009 Nobel Prize in Physics. He held dual UK and US citizenship at the time of his death in Hong Kong.

Charles K. Kao family background

The Kao family hails from a township called Zhangyan in Jinshan District near Shanghai, China1. As landowners, the family would have been considered prosperous. The sons of each generation would be well educated in the style of the time. My knowledge of the family genealogy only goes back to my grandfather.

Grandfather Kao Hsieh2 also bore the courtesy name Kao Ch’ui Wan3. He was a man of letters, famous for his beautiful poems, rendered in Chinese calligraphy; the combination of poetry and calligraphy is an art form of the east. A Confucian scholar, he was a book collector and also a prominent member of the Nan She (Southern Society). Other family members were also active in the society; Their aim during the 1911 Chinese Revolution was to help overthrow the ruling Qing dynasty. A museum now established in the city exhibits his work and also tells the story of the political activities in which the man took part. He was liberal.

Grandfather had four sons and two daughters. My father, Kao Chun Hsin, was not the eldest of the sons. The eldest would have remained in town to look after the family’s possessions and affairs; there these duties always fell. He was the third son. These sons grew up when modern times came to China. After a good education in Shanghai, my father went to Michigan Law School for a year. Before leaving for the United States, a marriage was arranged with a petite lady from one of the families of the social circle. She was left to await the return of the adventurous man. Coming from a family that was as modern as it was intellectually savvy, the new wife was educated and a poet herself.

Those were the years when offspring of the few wealthier middle-class families in China ventured to Paris, to London, to New York to deepen their experiences and studies. When they returned to China, they were greeted with great enthusiasm.

After returning from the United States, Kao Chun Hsin, then only in his mid-twenties, was appointed a Chinese judge at the International Court of Justice. He shared the bench with established judges from Western countries. With this prestigious appointment, he and his young wife moved to Shanghai, where they participated in the city’s social life.

Figure 2. 1942, young Charles Kao (second from left) with his family.

The first child born to the couple was a daughter, who was followed by a son two years later. misfortune struck. In a measles epidemic, both children fell ill and both died of complications, the older child at the age of ten, the younger at the age of eight. The mother was small-boned and of delicate, fragile appearance. The birth would not have been easy. In the years following the tragedy, she had miscarriage after miscarriage. I was finally born in 1933, fortunately a healthy child for my parents. My younger brother Timothy joined the family four years later.

Due to the earlier loss of the two older siblings, my brother and I lived a very spoiled and sheltered life. Nannies kept constant watch. Since my parents were busy with dinner parties and social events, we only saw them as if for a daily royal audience. Later, home teachers came to give us lessons. The basic lesson plans were readings from the well-known classics, the Four Books,4 which we learned to recite by heart. A second tutor taught English.

When I was ten years old, I was finally sent to school. The driver dropped me off in the school yard and told me to wait and someone would tell me where to go. I had never seen so many children running around so wildly in a crowd and standing there wide-eyed.

A bell rang and soon the playground was empty save for a lonely child. A friendly looking lady appeared and took me to my class. Maybe it was home tutoring, or starting regular school late, or an overly cautious and protective upbringing, but I certainly never became a talkative person. As an adult, I’m not always comfortable with small talk in social gatherings. I must have inherited my father’s gentle ways.

The elementary school I attended in Shanghai was a very liberal one, founded by scholars returning from an education in France. The children of leading families were enrolled there, including the son of a well-known man who is considered the top gangster of the underworld!

By now the family had a home that was within the French Concession. The International Settlements were located in an area within the city where various western powers had authority. These areas were generally kept away from the bustle of the metropolis and provided a haven from the human poverty of China. Locals called this area Shili Yangchang (a ten-mile strip of foreign glasses). When the Japanese invaded China in the 1930s, these areas were off-limits to the invaders.

The family was shielded from the horrors that unfolded. With the chaos of war, the courts were suspended and social gatherings dried up. My parents stayed at home more during this time and we developed a closer relationship with them. We played bridge and card games together to while the hours away.

Ending the war with Japan did not bring peace. Soon the Red Army, which had fought against the nationalist government, was at the gates of the city. My father made the decision to leave. In the family games of bridge, the topic was often discussed and the various options pondered. Moving to Chungking5 or going to relatives in Taiwan, or maybe there were relatives living in Hong Kong as well?

In 1948, after gathering up some belongings, the family boarded a ship sailing from Shanghai on a gray, gloomy, rainy day. The Bund’s famous waterfront slowly faded from view and that was the last we saw of our hometown for many years.

A brief stay in Taipei, the capital of Taiwan, convinced my father that Hong Kong would be a better place to escape. With the help of relatives on my mother’s side in Hong Kong, the family found a small apartment and my brother and I were enrolled at St Joseph’s College, where our cousins also studied. As English was the preferred language of instruction, the local dialect of Cantonese was not a requirement and I never felt the need to learn the language.

At 48, my father felt too old to study for the law exams that would qualify him to practice in Hong Kong. Instead, he took a job as a company legal advisor and also taught some Chinese law courses at local colleges. He became known in Hong Kong as an expert interpreter of ancient Chinese laws. There were still some cases of family inheritance and such matters that would require such expert advice.

I did well academically, but didn’t do much track or physical education during my five years at St. Joseph’s College. My former classmates in later life reported that they remembered me as a quiet person who didn’t get involved in the rough and tumble boy games. I almost got straight A’s in the matriculation exams, which enabled me to apply for admission to the University of Hong Kong. However, the university was still in some disarray after the war and not all faculties were functioning. I wanted to study electrical engineering. Great Britain beckoned and the British Council in Hong Kong was helpful. In 1953 I went to England on board a P&O liner.

I enrolled at Woolwich Polytechnic in London to take the Baccalaureate exams, which I passed with ease. I felt so comfortable at Woolwich Polytechnic that I did not apply to the other more prestigious colleges at London University and continued to study there for my Bachelors degree. In 1957 I graduated with a B.Sc. in electrical engineering. At that time, the degrees were awarded as first, second, pass or fail. Because I spent more time on the tennis court than with my books, my degree was a second.

It was necessary to find a job immediately. Financing my studies was a heavy burden for my father. I joined Standard Telephones & Cables (STC), a UK subsidiary of International Telephone & Telegraph Co (ITT) in North Woolwich, a factory across the River Thames. As a trainee, I was rotated through different departments for a year before realizing that I liked working in the microwave department. After two more years, I decided it was time to move on and applied for a teaching position at Loughborough Polytechnic.

During my three years at STC, I met and married Gwen, a fellow engineer who worked in the lab upstairs from my workbench. So we went to Loughborough for an interview, I got the job and we immediately started looking for a home. When we found newly built homes we put down a deposit and drove back to give our notices to STC.

However, it shouldn’t be

Someone in senior management had noticed how I had been working on the microwave projects and felt that the promise I was showing should not be lost on the company. The offer came immediately to allow me to transfer to the STL research lab in Harlow. As an added incentive for me to stay, a position would also be found for Gwen at the new location. Loughborough needed reassurance and solicitors went to work trying to get the bail on the house back. The offer was too good to pass up, and my future was destined to follow this new course. I stayed with ITT Corp and worked at various locations in the UK, US and Europe for the next thirty years.

In those years my parents emigrated to us in Great Britain in 1967. They were both in their late 60s and older at the time, but were still able to live independently. They were happy to have a grandson born in 1961 and a granddaughter born in 1963.

In 1970, the Chinese University of Hong Kong, CUHK, called. Would I come to college to set up an electronics department? STL agreed to grant a two-year leave of absence, which then became four years. I was able to see the first group of students graduating and also set up a graduate program. During this period, 1970-1974, annual summer vacations were taken to return to STL to keep abreast of developments in optical fiber research. It was also an opportunity to see my parents who stayed in Harlow.

By 1974, the project I had launched with the now famous 1966 article published in the IEE Proceedings had progressed into the pre-production development phase. Around them had grown an industry that went full force to revolutionize telecommunications systems around the world. ITT wanted me to be part of the team again for this endeavor.

So the young family was uprooted again, this time moving to the ITT facility in Roanoke, Virginia, USA. I was promoted to chief scientist, then to vice president and director of engineering, responsible for ITT’s electro-optical products division. During my years in the US, I continued to travel to other research labs around the world to discuss advances, promote the work, and keep up to date with the latest developments. It was a busy time. I used to drop by to visit my parents in the UK.

In 1976 my mother died at the age of 76. My widowed father, who visited Roanoke once or twice, preferred to live in Britain and this situation continued until he finally moved in with us in his eighth decade when we were back in Hong Kong.

By the 1980s, fiber optics was being deployed in large numbers around the world and the industry had grown into a giant. The communication capacity had grown exponentially. In 1982, I was appointed senior scientist at ITT, responsible for all research and development activities, and I moved to the Advanced Technology Center in Connecticut, USA. This position was specially created and gave me the freedom to do whatever I thought was important for ITT. To demonstrate the ultimate frontiers of optical communication technology, I advanced the Terabit Optoelectronics Technology Project to explore the technologies that could achieve terabit per second transmission capacity. The project, which involved a consortium of ten universities and institutions, aimed for a goal three orders of magnitude higher than the state of the art at the time. In 1985, I was appointed Director of Corporate Research at ITT. During this time, many innovations were developed by creative minds to take advantage of the increased capacity to send information through the system. The internet was born.

In 1986, CUHK called again. This time the request was to accept the post of rector of the university, the contract is scheduled to begin in 1987. In British terminology this post is called Vice-Chancellor of the University.

The second move to Hong Kong came as ITT Corp began selling all of its US engineering operations to Alcatel, a French company. After thirty years, it was a sad moment to say goodbye to long-time colleagues.

I was the third vice chancellor of the CUHK for nine years. It has been an interesting and challenging time, both for Hong Kong preparing to regain sovereignty from China, and for the higher education sector, which has seen massive expansion and quality improvement. During these years I strove to establish research more prominently as part of the normal work of the faculty, to establish contacts with many leading institutions in the US and UK, and to set the university on a path to becoming a better known institution. in competition with the best institutions. I was particularly pleased about the founding of the Faculty of Engineering, in which information technology played a major role. A faculty for educational sciences was also founded in these years. A number of research institutes were also established. The size of the university has almost doubled in just a few years, and a fourth undergraduate college has been established.

My job at university was to create space for people to grow. Essentially what I had done was create situations in which people would like to take responsibility. As a result, the university has grown as a whole: everyone contributes what they are supposed to do because they feel responsible for it and the environment allows them to do so. I created the space at the right time for talents to perform within the university and take them to a new level of development.

The rapid expansion of the tertiary education sector and the accompanying increase in government funding have enabled us to do many things to become a top university. The most gratifying change has been a scholarly atmosphere on campus—people are pursuing important things because they believe such things are important.

It was perhaps natural for my advice to be sought and for me to get involved in technology issues in the community, particularly information technology. I was able to play a role in setting up an internet exchange in Hong Kong (a bit of a novelty then and still a useful service today) and promoting the establishment of the Hong Kong Science Park.

My father died in 1996 just before I retired from university – a year before colonial Hong Kong was returned to China. My father’s ashes were brought back to England to be buried with my mother – in a cemetery in Harlow. After a year of speaking tours in Southeast Asia, I stayed in Hong Kong and started my own consulting company. I have been called to a number of companies as a non-executive director.7 In 2009 I moved to California to be closer to my two children.

Vignettes from childhood and working life memories

I had an argument with Lo in my classroom. We attacked each other with our calligraphy brushes, smearing black ink on our faces and hands. The teacher was shocked. Lo, my mother warned me, was the son of a wicked man. I should be careful not to argue with the boy again. Otherwise the school was fine. We sang French songs. The calligraphy teacher was very encouraging. This stroke is beautiful and is marked with a red dot. But this one is crooked and unbalanced, it gets two red points!

I made a good friend in elementary school who liked to play with me at home. We made our driver buy all sorts of chemicals. We read scientific journals, experimented together, and made phosphorus mud balls to throw at stray cats and dogs. The mud balls would explode with a bang, scaring the animals to death! From glass bottles and the like I would make the funnels and beakers needed. I had bottles of cyanide and concentrated acids. One day when I was boiling nitric acid, the bottle exploded and the concentrated acid spattered onto my little brother’s pants. It burned the cloth off completely but luckily didn’t end up on his skin! My parents were furious and confiscated all my chemicals including the cyanide. I wonder where they dumped that stuff.

One day my father brought home a large round yellow disk of food that he told us was called “cheese” that foreigners ate. Food was scarce so we ate it but it tasted very weird. When we walked outside, we sometimes passed a large, tall building with Japanese soldiers standing outside the door. My parents told us to hurry by as people were being killed there and bow to the soldiers.

It was sad to leave Shanghai, but I was fourteen years old and ready for new adventures. The war with Japan was also exciting. As we crouched under the desks, we could hear the aerial combat in the sky above us. Peering from below I even got a glimpse of the American planes chasing the Japanese planes and diving in after them!

So the Shanghai waterfront faded away and we went to Hong Kong. The schooling there was easy and the book work was not difficult at all. The class went on a field trip and some of my classmates got lost in the hills until it was pitch black and they could see “tigers”! I wasn’t in that group, but now when we have a class reunion, the boys will relate their adventures with enthusiasm and lots of laughter. So my years in Hong Kong flew by and I was set to embark on my next adventure all by myself.

On the ship to England to study electrical engineering, I shared a cabin with three others. Two worked for the Hong Kong government and went to England to take some courses relevant to their job, meteorology and water treatment respectively. The third was a professor of mathematics. During the six-week voyage, the professor taught me quantum mechanics. He also took some other young students and me under his wing. When we stopped in Singapore he accompanied us to his friend’s house and taught us all to eat hot curry and wash down the fiery food with beer.

I was nineteen years old and had never left my family to be alone before. Everything was a new experience. To put my foot on the ground in Port Said so I could tell myself I’d been to Africa to cross the Strait of Gibraltar and say I’d seen Europe and the Sahara to find England a cold and gray land ! I didn’t think eleven long years would pass before I would see my parents again.

The British Council staff met me and arranged accommodation for me with a landlady in a house on Plumstead Commons, near Woolwich Poly. Her house was old and big, with rooms for several lodgers. We all ate breakfast and dinner together under the stern eyes of the landlady. After World War II, food was still scarce and the slices of meat served at dinner were so thin that they were transparent when held up to the light! After such a meager meal we all moved out into the ‘fresh air’ but the real reason was to buy some fish and chips which we hungrily taunted on the way back up the hill. The habit remains; I still love fish and chips.

After graduating from Polytechnic in 1957 I joined STC and had to walk to work every day through the tunnel under the Thames. My first project was to build an amplifier and I got my books out to study the theories. My boss came over and told me to put the books away, just do it. Schoolwork is designed to train the brain to think intelligently. There was no need to revise the theories any more!

I met my future wife at work. She was an engineer in the coil department. We married in 1959 and our children were born, a son in 1961 and a daughter in 1963. At that time we were living in Harlow and working at STL.

The research was fascinating work and in 1966 I published the now famous seminal paper Dielectric-fibre Surface Waveguides for Optical Frequencies. This research would spawn a whole new industry over the next twenty years.

People asked me if the idea came suddenly, eureka! I had worked on microwave transmissions since graduating. The theories and limitations were ingrained in my brain. I knew we needed a lot more bandwidth and I kept thinking about how this could be accomplished.

Transmitting light through glass is an old, old idea. It has been used in years past to shine a light through a glass rod for entertainment, for decoration, for short distances in operations, but it has not been possible to use it over the long distances required for telephony. Light passing through a glass rod fades to nothing after a very short distance of a few meters. Efforts by many research labs to find a way to transmit light long distances have been desperate as the public, spurred by media reports of hopeful technological advances, expected increasingly exotic services.

I played around with what resulted in the light not penetrating glass. With the invention of the laser in the 1950s and subsequent developments, there was an ideal light source that could emit pulses of light in a digital stream of zeros and ones, represented by off and on states of the pulse.

Ideas don’t always come about in the blink of an eye, but through diligent trial and error experiments that take time and thought.

Related searches to Who Is May-Wan Kao Details To Know On Charles K. Kao Wife

Information related to the topic Who Is May-Wan Kao Details To Know On Charles K. Kao Wife

Here are the search results of the thread Who Is May-Wan Kao Details To Know On Charles K. Kao Wife from Bing. You can read more if you want.

You have just come across an article on the topic Who Is May-Wan Kao Details To Know On Charles K. Kao Wife. If you found this article useful, please share it. Thank you very much.

Articles compiled by Bangkokbikethailandchallenge.com. See more articles in category: DIGITAL MARKETING